Euro 2016 and the topic of possession

Here is a link to a very interesting article about possession.

http://www.skysports.com/football/news/11096/10500158/how-has-football-changed-possession-is-no-longer-nine-tenths-of-the-law

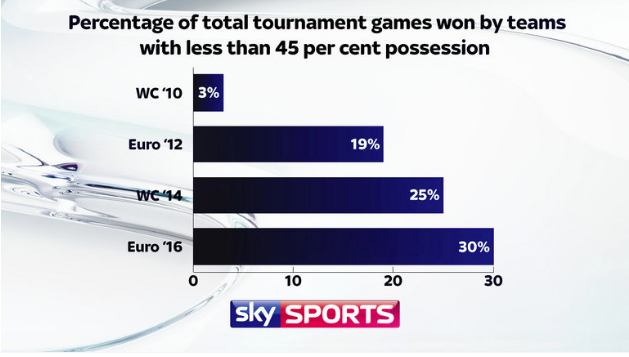

More wins with less than 45% possession

The Sky Sports article above, by Gerard Brand is very interesting because in the discussion about the value of possession he shows over time how teams have won more games with less possession than their rivals. Teams with more possession still win more often but it is not a guarantee of success. Statistics will tell you something about possession but not everything. Statistics need to be considered in the context of the game to better understand what they mean. The graphic below from the Sky Sports article shows how the chance of winning with less than 45% possession has improved over time from 3% in the 2010 World Cup to 30% in Euro 2016. It also means that there is a 70% chance of winning with more than 45% possession, which provides a good incentive to dominate opponents.

Other benefits from keeping the ball

We have known for some time that dominating possession is not the key to winning matches so are there other reasons for trying to keep the ball? Evidence shows that in most cases teams that dominate possession still win more games than they lose and then along came Leicester City, who won the EPL doing the opposite, which proves there will always be an exception to the rule. Over time Anderson and Sally [1] showed teams that consistently had more possession than opponents did not get relegated in the EPL. Another reason is when a team keeps the ball their opponents cannot score. Gerard’s article certainly raises some questions about possession rates and winning matches but could it be that more teams at the Euros just spent more time defending deeper rather than pressing higher up the field to win back the ball?

Goals from possession regained in the Back Third and Own-Half of the field

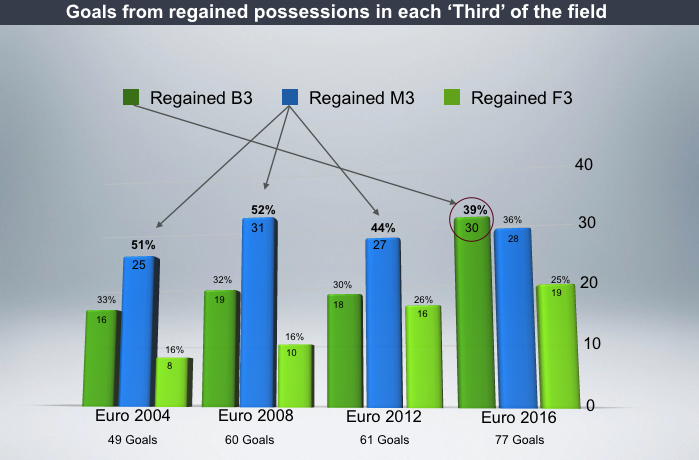

The percentage of goals in Euro 2016 from regained possession in the Back Third was 39% compared with 36% in the Middle Third and 25% in the Final Third. This was the first time the majority of goals did not come from regained possessions in the Middle Third. Figure 1 shows the results for the last four European Championships.

Until Euro 2016 the highest percentage of goals came from regained possession in the Middle Third. The percentage of goals from regained possession in the Back Third has been higher than the Final Third in each tournament and the percentage of goals from regained possession in the Final Third increased quite considerably in 2012 and 2016 compared with 2004 and 2008.

Despite an intention to press higher up the field by teams in 2012 and by some in 2016 the number of goals from regains in the Middle Third has been consistently higher than in the Final Third. This evidence shows that pressing high does not equate to winning the ball back in the Final Third. In fact the vast majority of regained possessions in the Final Third come from clearances and throw-ins, not from dispossessing opponents. In Euro 2016, 13 of the 19 goals from regained possession in the Final Third in Open Play were from clearances.

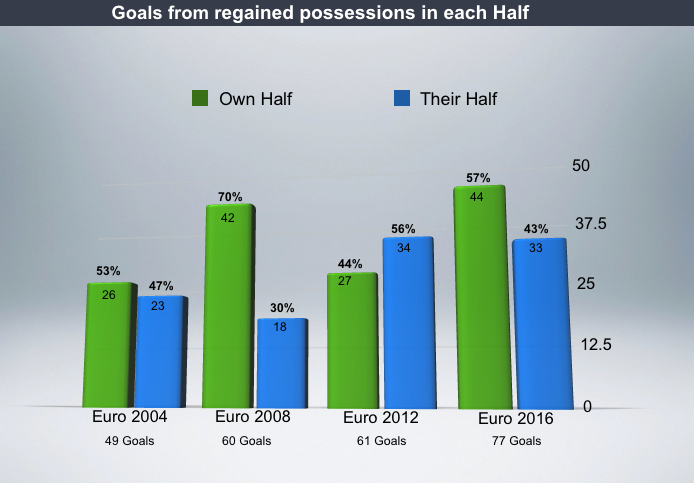

Figure 2 shows the percentage of goals from regained possession in each half of the field. The only time there was a higher percentage in the opposition’s half was in 2012, so Euro 2016 saw a switch back to what happened in 2004 and 2008 where more goals came from regained possessions in the teams’ own half of the field.

All teams spend a certain amount of time defending in their Back Third. Some teams choose to defend deep as their preferred strategy while others may only do it when they are forced to defend deep by the opposition. Euro 2016 saw the highest percentage of goals from regained possessions in the Back Third for the first time in the last four tournaments so were the goals scored in similar ways to the past?

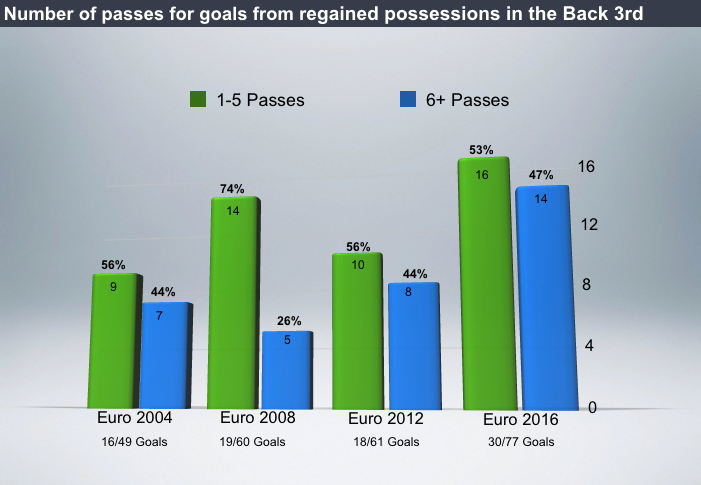

Figure 3 shows the goals from passing sequences of 1-5 and 6 or more from regained possession in the Back Third.

In each tournament there have been more goals from shorter rather than longer passing sequences from regained possession in the Back Third, the question is why?

Speed of transition

We know that teams are vulnerable to concede a goal if the opposition attack quickly when they win back the ball. If that happens closer to the opponent’s goal there will be no need to make a lot of passes. In Euro 2012, for example, Spain scored ten goals in Open Play and eight were from regained possession in the opponent’s half of the field. One might expect more goals to be scored with fewer passes from regained possessions in the Final Third and that is definitely the case; 18 of the 19 goals in Euro 2016 from regained possession in the Final Third were scored with five passes or less.

The reality is that there are many opportunities to attack quickly from everywhere on the field but doing it from the Back Third is just harder than in the Front Third because of the distance from goal. When teams cannot or choose not to attack quickly they have no choice but to play at a slower pace and work the ball through the opposition’s midfield, which is quite difficult to do and usually requires more passes to be made while possession is retained.

The key area on the field to score goals

At the highest level 90% – 95% of goals in Open Play are scored from within 23 yards of the goal. For example, in Euro 2012 only 2 out of 61 goals (3%) were scored outside 23 yards, in 2016 the figure was 4 out of 77 (5%). The task for players is to get the ball, from wherever they regain possession, to within 23 yards of goal or they will not score many goals. The really interesting questions are how and when to do it quickly and how to be creative against a packed defence once the opposition has had time to regroup? That’s nothing new but the poor goals per game ratio of 2.1 per game compared with 2.5 per game in 2012, proved that Euro 2016 was not as exciting or creative as previous European Championships.

Where to next

If possession is finally accepted for what it is and we recognise that every team needs to have it and preferably with more than less the important decisions in the game will be focused on two situations. The first relates to recognizing when it is ‘on’ to attack quickly and then doing it with total commitment. The second is to improve the success rate of playing through teams regardless of whether they defend high, in the middle or ‘park the bus’ in the Back Third. I know it is easy to say and difficult to do but coaches will have to think ‘outside the square’ because current practice is very predictable.

Suggestions how to do it?

First of all we need to develop more players who can dribble and beat defenders, but that’s a longer-term project. Secondly, players need to be better educated with regards to how they position themselves on the field so they can see team mates, opponents and the ball as often as possible. I was so disappointed in Euro 2016 to see so many players who stood or ran into positions ahead of the ball where they had their back to goal; that has to change. When players have their back to goal they cannot see opponents and cannot pass the ball forwards, both are counter productive to causing defenders problems. Thirdly, players need to be taught how and when to make good forward runs and that they should be constantly looking for opportunities; I did not witness much of that at Euro 2016, apart from France, Spain and Germany. Making forward runs is greatly influenced by body positioning and something that players rarely do with their back to goal.

Reference

1. Anderson, C. & Sally, D. (2013). The Number Game: Why Everything You Know About Soccer Is Wrong. Penguin Books